This long letter to you was, for many months, only about love, but this was not a very interesting letter. Very few people can write well about romantic love. After a few attempts, I decided I am not ready to throw myself on that pyre; I have too high an aversion to shame! And things are more interesting when approached obliquely, anyhow, when the idea is arrived at from the side. I wasn’t really ever writing about love, but about its attendant effects, its signs of arrival, its disturbances and phase changes in me. For one, I learn to pay the closest visual attention to a person I feel love for; I remember details I either find or imagine few bother to see, because care might be noticing a person at such a depth of detail and involvement you hope they might spend for you, notice you within. This practice of valuing qualities that others might not notice is a learned practice that can be applied anywhere.

So this missive to you then became a litany of other kinds of love that are just as important and profound and necessary as romantic love, the other kinds of intimacies that emerge from noticing detail. It seems that an entirely new language can be built out of paying violent attention and violent care, one that can identify hidden pain, that can make repressed trauma and emotional states legible, that allow for us to recognize when those close to us carry burdens they must hide to survive, to function, to pass. Each time I can read a situation for what is buried, that I can read a face for what is locked away or veiled, shrouded, or a friend can do this for me, we build out the space of possibility between us. It seems important to focus on the direct connection between seeing and care right at this moment when seeing things clearly, and processing for meaning, feel fractured and difficult tasks.

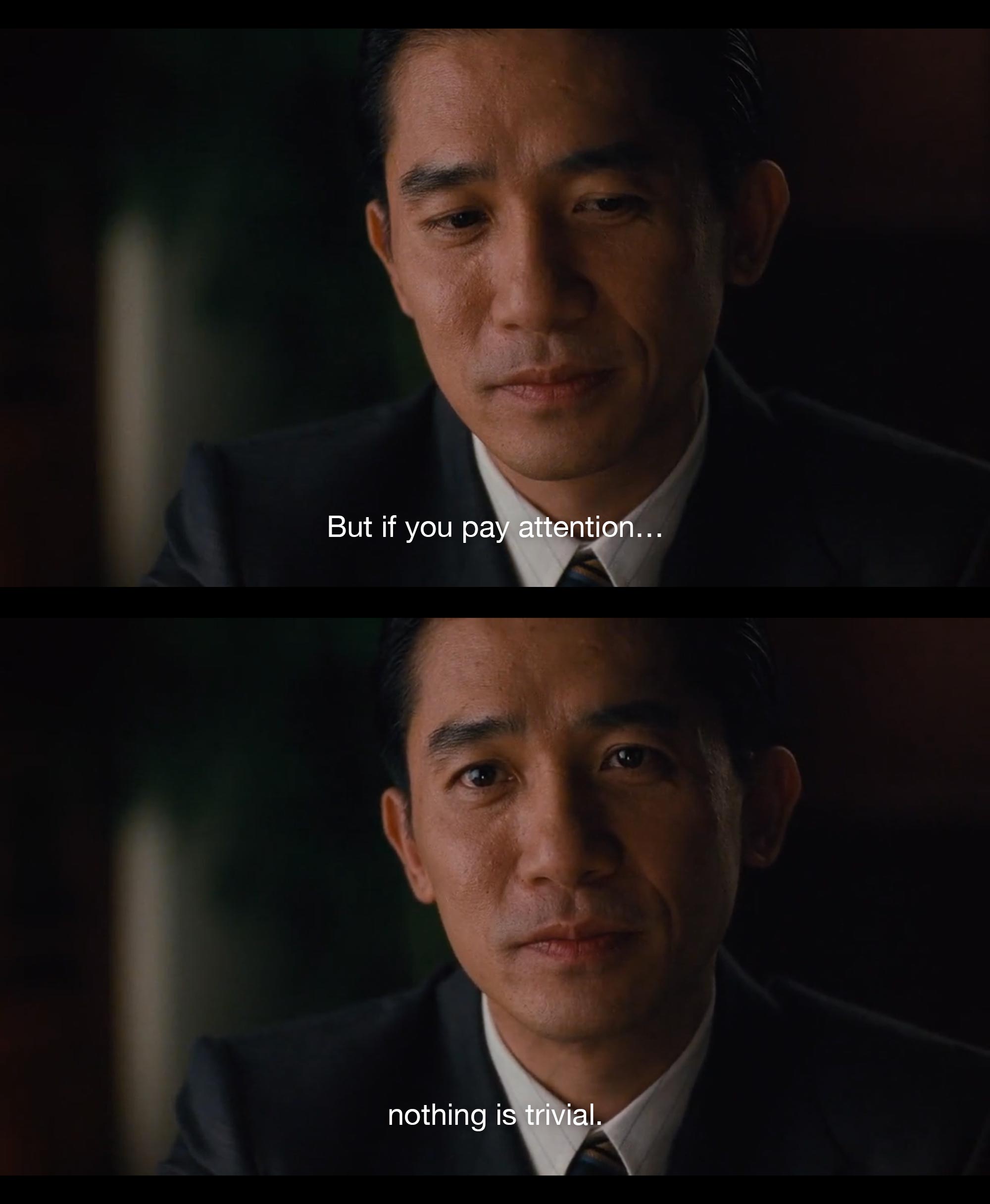

“Everything around you can be analyzed in terms of its visual presence,” wrote Roberta Smith in 2009. I recently met up with a friend from graduate school who said it made sense I ended up writing not just fiction (“just” fiction) and instead about art in a fictional way. He said he remembered that we had sat in a workshop together parsing the images in an old story I had submitted, more than its plot or characters. We then talked about always needing a vivid enough image before putting any words to paper, how the image fuels and drives the whole, especially in criticism, to keep abstract philosophical meanderings tethered. Open with an image and close with an image. For this letter, I opened with the image of Tony Chiu-Wai Leung in Lust, Caution, as he looks up over dinner to say to his companion, “If you pay attention, nothing is trivial.” The camera lingers on his face, his expression passing through dozens of changes within a minute.

I remember faces and the feeling of presence more than what people say. Words dissipate before presence. How long can you look right in your friend’s face and hold their gaze? “Their presence is unbearable; I can’t look directly at them,” my friend tells me, trying to describe some person who had temporarily invaded her brain.

Digital technology is force-changing our perceptual ability. Our collective image literacy is has grown so complex. Old structures of spectacle are changed by the dominance of drone vision and Google Image mapping, and tagging, and our own emerging relationships to this god eye.

We take on our localized versions of the all-seeing gaze, our own pair of high-class binoculars to look into the apartments of unsuspecting people, scaling, zooming on them cooking and dressing, sweeping, pacing, all in high definition. We can shuttle back and forth between three-dimensional renditions of our own skin cells out to aerial views of the streets we sit in, in our skin, reading, out further to past renditions of the city when we did not live in it and our existence meant nothing to anyone in it. We can access terrible details we were never supposed to have access to, vistas we have not earned, opened up to us with uncanny precision. An intimacy with every object under the sun.

⋇

In the weeks after moving to New York this past fall, I felt buried under my books, which I have been hauling around across the country and up and down the East Coast for a decade. New Haven, Chicago, Boston, Iowa City. The majority of my books are in my parent’s house, held hostage in ten white book boxes until I “go to retrieve them,” an event horizon that recedes each year. I hold onto this clutch of about one hundred and fifty books in my place in Sunset Park for their sentimental value.

My nostalgia is not for the books, but for a kind of literary reading, a slower time when my head felt more clear, and focus came easy. Like most good former English literature students, I read all of the long, dense, beautiful European novels for pleasure. I loved and love George Eliot and Stendahl and I had the attention span to sit through Anna Karenina uninterrupted and take notes in the margins. All the books you are supposed to read. In contrast, last year, it took me over eight months to finish A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara, though I’ll grant its excruciating slog through ritual abuse also slowed me down.

The locus of art and “great truths,” whatever those are, has shifted to the digital, to the beautiful noise of the Internet, the chaos of meme magicians who frame a world of complex logic.

Even though I loved these books at one point, they’ve now become an annoyance, cropping up under my desk, tripping me up, no matter how many intentional To Be Read stacks I make. I have tried sorting through the good books and the bad, the books that were good but are now bad, the books I’ve bought in full hope of reading but never did. I have a “shelf of shame” of books I can’t admit to owning but also can’t bring myself to throw: Žižek, Naipaul, who was my favorite prose writer but now I can’t read without thinking of the kind of abusive and violent person he was to the women in his life.

Really, when am I going to sit down and finish Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain? There’s a sanitorium in it, right? That seems interesting. Why must I read the “great canonical” stories of family, culture, imperialist and civilizational conflict, when I don’t identify with the families, or the culture, when my own culture was subject to colonial oppression, erased, denied, diminished, to the point I don’t always recognize its value and beauty unless it is relearned, or even learned for the first time? I know, already, how the fabric of daily mental life can be shaped by a fractured social and psychological inheritance that is life in the mangled diaspora. I know enough about racialized conflict as it flows through my blood, so why, really, do I need to read Heart of Darkness again?

I just can’t seem to place myself back in contemporary Victorian society when our own society is burning. Plenty of books I thought I would love forever no longer work for me. And my changing personal politics muddle the emotional attitude towards old authors, so the vertical tower of books I’m ambivalent about only grows higher.

There is a reason “people don’t read” books very much anymore and publishing collapsed, and it isn’t because, as institutions and cultural elitists decry, people are not interested in art or beauty or the great truths of our time. The locus of art and “great truths,” whatever those are, has shifted to the digital, to the beautiful noise of the Internet, the chaos of meme magicians who frame a world of complex logic, the logic of simulation and collective intelligence that seems to shape and generate unprecedented movements and action, if yet under the aegis of a divine stupidity.

Further, the quality of my attention has changed dramatically with a decade of nearly daily ritual use of the Internet for research, for work, for gaming, and for socializing. What and how I read has changed, as we have all trained, consciously or unconsciously, to sift through information online with deadly efficiency. Information, at total odds with narrative, or the painstaking, labored research and criticism that traditional magazine culture was built on. The more interesting practice online might be gleaning suggestive, if partial, half-truths, or clues, or contextual details, over a perfect story. In the writerly goldmines of forums, and comment threads, author’s hidden blogs, TinyLetters, even Livejournal, there’s more to be learned about human experience that relates to how we might learn to live now, I feel, than in great canonical works.

The moving process also revealed an outcropping of new texts that feel more like beacons. Jeanette Winterson’s Art and Lies; the essay collection Possibility: Essays Against Despair, and Nocilla Dream by Agustín Fernández Mallo, which I found through the newsletter of Warren Ellis, a writer whose practice embodies the kind of promiscuous, rangy, and democratic reading and listening that we need.

I have been thinking about my own relationship to the canon after a friend recently described to me how he “looks for the radical writers” of each age throughout history. We were debating why one needs to read great writers, or not, and his argument was that one should just follow one’s interest and intuitive understanding of what is compelling. If that happens to be people who were radical for their time – like, say, William Tyndale, or Osip Mandelstam – then those people made a good framework to organize one’s interests around.

I started to think about the tension between craft and mastery. Who is a great writer, and what makes a great artist? Why were the “radicals of their time” so often living in neglect and disrepair? How did I learn to love both the canon and everything outside it? You can love Borges and Calvino and Lispector, but also love all the other “cultural makers,” the cartoonists and game designers and graphic novelists who don’t always get their due for making great art, and are usually scoffed at and mocked. It isn’t like people become more open to the poetic possibility of many different genres over time; I just see people demonstrating less and less imagination and curiosity and generosity as they get older. This is enough to cause a string of existential panics. Being open needs daily spiritual maintenance and reflection. I was a classical piano player for many years and so my music references, too, were canonical. But it took time to value everything from Scriabin and the romantics to surrealist fiction and horror, all along the same register.

I wonder about how one finds experimental music and experimental art when both are often not stressed at any point in school. For me, they were arrived at through noticing odd, twisted moments, through following a feeling of fundamental strangeness. I had to learn to organize images and sounds that suggest the uncanny, total defamiliarization or ostranenie. I think the Internet has helped us find these moments of possibility and rupture more quickly – more on this in a moment.

But it took a long time to learn to put them all on the same level. It took a democratizing and undoing of academic education to try and appreciate what true radicality and vision are. Only very slowly, off the campus, did I begin a path towards what I am truly most interested in: speculative poetics, speculative fiction, and the history of experimentation.

⋇

I joined Twitter in 2009, and started using it actively in 2010, when I started editing games writing. I needed a way to find people in games – designers, programmers, engineers – and they were some of the most active and ardent users of Twitter. We shared Let’s Plays and run-throughs; I could ask for basic knowledge and instruction about builds and engines and platforms. No matter the time (I suffered severe insomnia in that period, and shudder to think of the mornings I’d be up at my computer at 5 a.m.), there would be someone up on Twitter. They would emerge from the void with a highly technical, useful answer, sourced from their own immersion in games I couldn’t imagine approaching. They’d played Skyrim’s eighty to one hundred hours several times through; they were generous with their time and advice.

I took a break, to return again in the abject Boston winter of 2013. I started to log on with urgency because I was blocked in my writing. I started to find poets like Bhanu Khapil and Jackie Wang who both use Tumblr and Twitter actively, almost daily, documenting moving and interesting moments in their days: bird’s eggs in trees, the feeling of a sunset in Reykjavik:

Spring morning, Monday, Colorado: three trees. Two in blossom. One reflected. And one of them has laid a scarlet Shivling (cosmic egg). pic.twitter.com/OLFwVYpKWU

— bhanu kapil (@Thisbhanu) 3 aprile 2017

Im on the bus to Reykjavik & tho it’s after 1am I can still see the lupine flower fields casting violet across the floor of the eternal dusk

— Jackie Wang (@LoneberryWang) 23 giugno 2016

Or, there would be inspiration:

your greatest beauty

is a form of hope

imparted to all who talk to you,

that life yields its secrets

to the careful searcher.

—Diane Wakoski— Jackie Wang (@LoneberryWang) 9 aprile 2017

Soon after finding her Twitter and her poetry, I would happily get to know Jackie. She is a remarkable thinker and human being. We both were living in Boston. I am not sure I ever told her how important her Twitter was to me, but I am saying it now. Those times were mentally and emotionally extremely dark. Seeing her generosity with her insights and perception, how she shared her intimate thoughts in public, helped me feel less alone, and hopeful about the project of writing.

Lauren Berlant calls this practice a development of an “intimate public.” In seeing others think aloud in public, make digressions and linger in the space around an unfinished idea, a poet can build a kind of shadow community joined through affect. In inviting them to see along with her, she also allows other observers a peculiar access to their own selection of detail and process of framing.

Twitter was ever an interesting way to build a very small if fragile community. I found people across the world who could explain Afrofuturism at the drop of a pin or send me a copy of Hyperion they didn’t want anymore or write some xenofeminist poetry in Shodan’s voice on the fly like it was nothing. Deep nerd hours! I do not mean to be twee or sentimental, but I found people who understood my interests in the exact same way, who I didn’t have to explain much of anything to, who I could be completely myself around, on Twitter.

⋇

I recently re-read “You Are Invited to Be the Last Tiny Creature,” the opening of Where Art Belongs, an essay in which Chris Kraus patiently eulogizes the start of a punk-art gallery, music label, and collective space called Tiny Creatures in Echo Park, Los Angeles.

I think of writing letters. There was a different mental space, before the endless performance piece that is performing subjectivity online and in public, of turning one’s intimate thoughts out for consumption in a feedback loop from screen to brain back to screen again.

Tiny Creatures was a vital space and scene with a sort of “feral quality” that attracted dealers and admirers. As Kraus describes it, it folded under the pressure of success, attention, and big money. Kraus covers the strange religious background of the unwavering founder Janet Kim, who wanted a community out of her gallery above all, not fame, not money, and not connections. It’s a fascinating account of Echo Park before gentrification, and also a portrait of the hungering, cannibalistic hunt of older art world figures for the energy of skaters, bikers, and punk kids.

Kraus gives us a concentrated portrait of intimacy pre-Recession, or as we might remember intimacy. I think of big lawns in small towns. I think of small and dirty dives with poets reading to their close friends. I think of writing letters. There was a different mental space, before the endless performance piece that is performing subjectivity online and in public, of turning one’s intimate thoughts out for consumption in a feedback loop from screen to brain back to screen again.

This is likely my romanticizing, as I have trouble seeing past the alienation of the present moment, and that moment was almost definitively alienating, as well, just in different ways. And there’s fetishizing of digital dualism in this romanticization, as well; we now have many models for understanding our relationship to technology, one being that offline and online are not inimically opposed. One mode flows right into the next, and they are both expressions of the same living. As Nathan Jurgenson writes, social media is not a separate space nor is cyber-life (the quaintness of that prefix, cyber-!) any different from real life. But there are key, obvious differences in the affordances of digital communication compared to in person, not least the different affective spheres built.

What kills me about Kraus’s essay is her reverence and respect for detail. She writes in this miraculous way that assumes significance of every character involved. She is unwaveringly patient and sober with the young and energetic characters, recounting their anecdotes and memories with care. That they were 21 and trying and failing is just as important and significant as being 45 and very successful. She turns each person over and over in the light; she never patronizes. In reading this essay, I feel the value of looking at one’s own start with some grace and generosity. Everything is significant, everything is important, if you are paying attention.

⋇

I don’t think there’s a chance of reclaiming one’s pre-Internet brain. Our minds have been shaped irrevocably by continual exchange and interaction with the Internet. Of course, we can change our relationships to the Internet, redefine our position and focus within it, but the fantasy of total Luddite disconnection seems both implausible and one of immense privilege.

Navneet Alang wrote a beautiful piece on the psychological impact of using Twitter in Real Life last year, which prompted me to revisit Alexis Avedisian’s essay “The Economy of Nostalgia.” Alexis’s essay is one of my favorites about our lives online; she asks for a nuanced view of why we stay on platforms despite their extraction, their obviously tailored addictive modes.

She argues our presence on them says much more about what we want and desire for ourselves, about our shared loneliness, about the desire to be seen and heard and understood when we feel displaced and cut off from ourselves. Alexis writes, “Nostalgia is an amalgamation of human sentience becoming present from the past, automated in a value system designed specifically for the ephemeral.” And speaking of Penny Goring’s DELETIA project, Avedisian continues:

The self is rendered a prism that wards off the ghostly promises of data immortality as much as it fragments the lived experiences that make up the whole of a person. We are taught that we will age out of passion and sexuality; we are taught to fear this day as much as we fear the youth that emblazon so well the lives we may have already lived. Using her age as a platform for empowerment, Goring teaches us that it does not matter when an image of ourselves is published, but that it has been disclosed fearlessly from the economy of nostalgia. The body holds inherent obsolescence, like an iPhone or a Facebook service, but selfhood cannot be scheduled for depletion. The self is not a product to be upgraded, but an archive to be cherished, with or without reminders from Facebook. “DELETIA is a way of protecting myself, forgiving myself, making peace, and coming to terms. I am the sum of everything I was, am, and will be; it’s all of me existing at once.”

In some ways, being on Twitter felt like emotional self-flagellation, pure indulgence in the exquisite pain of seeing all of oneself “existing at once,” getting to review all of one’s flaws, mistakes, and miserable longings with some remove and perspective. The downsides of platforms – the sloppy thinking, reactivity, and easy validation – were outweighed by the feeling of a strange turning of attention from disconnect to something much more powerful and true and representative of our moment. Sure, we are increasingly atomized, cut off from one another, suffocating in neoliberalism, yes. But we have found to leverage the myopic narcissism of platform engagement to gain some kind of understanding, mirror and reflect ourselves, create multiple personas to pour one’s real thoughts into, and work out a coherent-seeming identity while being continually seen.

Somewhere in the months of drafting different sections of this letter, I jammed in:

TIME IS PASSING A DECADE HAS PASSED TEN YEARS AGO STILL FEELS LIKE YESTERDAY!

When I think of my childhood I think of very small rooms with a good lock from inside, usually, in which I drew and painted and wrote and gamed, alone. Maybe it is sad. Probably. I do not really care. It was what it was: then, a radically impoverished, violent, and painful home existence. When you are a child of parents from a war, this means alienation, internalized epigenetic trauma, and for most South Asian girls and boys living in America, daily physical and emotional violence that must be balanced with performing at the highest level for fear of more repercussions. It’s a cool vibe.

In my room, my one sanctuary, I learned to block out that world, and I focused on the carpet and the smell of paint, my Gateway computer, and what was outside the one window I had. I dreamt about times that would be better. That isolation forced a kind of attention to what was closest at hand, and something like a crazed focus on liminal details was probably generated there in that room. I knew how many cardinals lived in the trees. I knew what time my neighbor, the dad, the husband, came outside to smoke. He wore khaki shorts and blue polo shirts. He looked at the hill behind the apartment building we lived in, as his children inside screamed and broke things.

I see now that this early cradle of alienation – social, economic, and cultural – forced me to find a new home in what I loved to read and listen to, in the abstract. The world I wanted to be in was not in sight, so it had to be elsewhere and beyond. I found comfort in mapping what is known and unknown, in futurity, in the idea of a more just and ethical world, whether here (in 2017) or somewhere past Saturn.

I credit my alienation for developing my attention to the references and creators and spaces that are often ignored, disregarded, or unseen. I feel this early alienation, cognitively helped me be predisposed towards any kind of essential strangeness. Life in a family in constant cultural conflict in one’s new home country means one is always seeing all sides of any situation: how you are seen, how others see you seeing them, how you speak, how others speak, their intention, your intention. I developed a map of what was known and unknown, what knowledge is correct or incorrect. I live, as others in the First Generation all live, in what feels like multiple bodies at once, because one’s visibility is so very high. The outer, performative, and inner, flawed, broken, and real. “When I’m fucked up, that’s the real me.”

This hyper- self-consciousness, a visual attuning towards self and others, helped me orient towards what is not known, meaning, what people miss when they see you, what you must continually narrate and insist on: the depth of your inner life as you feel it, your dreams. The possibility of all the other worlds you believe in, which have no relation to the present. You insist on everything no first impression can possibly suggest alone, on everything your first impression possibly erases in the minds of some, or many.

⋇

Peel your own image from the mirror: this is a line from Derek Walcott’s Love After Love. The famous poem describes a future time in which the reader will recognize herself, will greet herself at her own door. I also read it as finding an intimacy with oneself, seeing the details of oneself clearly. You might call on yourself to see all the details of your life from a remove. The poem’s listener moves from this simulated drama of restoration back into herself to hear her own twisting changes. One day, surely, she will also see herself clearly in the mirror, past her own painful split image, her many split selves, to be made in herself again.